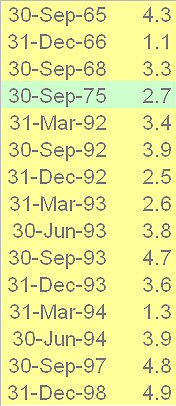

As you see, mostly it was the nineties, with one instance in 1975 and three times in the sixties. The average rate for the whole series up to December 2006 is 13.47%. So the hand-mill never stops grinding.

As you see, mostly it was the nineties, with one instance in 1975 and three times in the sixties. The average rate for the whole series up to December 2006 is 13.47%. So the hand-mill never stops grinding.

But should it? Wikipedia gives an account of recession and the Great American Depression, and notes that during the latter period the money supply contracted by a third. Great for money-holders, bad for the economy and jobs.

This page points out that we tend (wrongly) to think of a period of economic slowdown as a recession, and says that technically, recession is defined as two successive quarters of negative economic growth. By that measure, we haven't had a recession in the UK (unlike Germany) for about 15 years - here's a graph of the last few years (source):

Mind you, looking at Wikipedia's Tobin's Q graph, the median market valuation since 1900 seems to be something like only 70% of the worth of a company's assets. Can that be right? Or should we take the short-sighted view of some accountants and sell off everything that might show a quick profit?

Nevertheless, it still feels to me (yes, "finance with feeling", I'm afraid) as though the markets are over-high, even after taking account of the effects of monetary inflation on the price of shares. And debt has mounted up so far that a cutback by consumers could be what finally makes the economy turn down. Not just American consumers: here is a Daily Telegraph article from August 24th, stating that for the first time, personal borrowing in the UK has exceeded GDP.

The big question, asked so often now, is whether determined grinding-out of money and credit can stave off a vicious contraction like that of the Great Depression. Many commentators point out that although interest rates are declining again, the actual interest charged to the public is not falling - lenders are using the difference to cover what they perceive as increased risk. Maybe further interest rate cuts will be used in the same way and keep the lenders willing to finance the status quo.

Some might say that this perpetuates the financial irresponsibility of governments and consumers, but sometimes it's better to defer the "proper sorting-out" demanded by economic purists and zealots. History suggests it: in the 16th century, if Elizabeth I had listened to one party or another in Parliament, we'd have thrown in our lot with either France or Spain - and been drawn into a major war with the other. We sidestepped the worst effects of the Thirty Years' War, and even benefited from an influx of skilled workers fleeing the chaos on the Continent. If only we could have prevented the clash of authoritarians and rebellious Puritans for long enough, maybe we'd have avoided the Civil War, too.

So perhaps we shouldn't be quite so unyielding in our criticisms of central bankers who try to fudge their - and our - way out of total disaster.

1 comment:

great piece this one.

Post a Comment